Remembered by many for their efforts in women’s suffrage, the United Farm Women of Alberta (UFWA) were prolific lobbyists throughout the early half of the twentieth century. However, their influence extended far beyond ensuring women’s place in politics. Not long after their formation, the UFWA gained the reputation for being a respected voice advocating for the welfare of Albertans, particularly those in rural communities. After amending their constitution in 1913 to allow equal terms of enrolment to women, the United Farmers of Alberta experienced a gradual increase of women attendees. In 1915, with a much larger number in attendance, the 58 present women delegates formed their own off-shoot of the organization, The Women’s Auxiliary to the United Farmers of Alberta.

The branch’s first session was held on January 19th, 1915. Unsatisfied with the status of “auxiliary”, the fledgling organization’s newly appointed president, Irene Parlby, successfully petitioned for a reclassification and renaming of the association. By 1916 the United Farm Women of Alberta was firmly established and immediately set to work addressing what they believed to be the province’s pressing social issues, one of the most critical being medicine. The province was quickly falling behind in terms of healthcare. Alberta had the highest rate of maternal mortality and the fourth highest for infants under one year of age. From 1919 to 1924, only 7% of births in several rural municipalities had access to medical attention owing both to the lack of physicians and other trained medical professionals, and the high costs of those who were available.

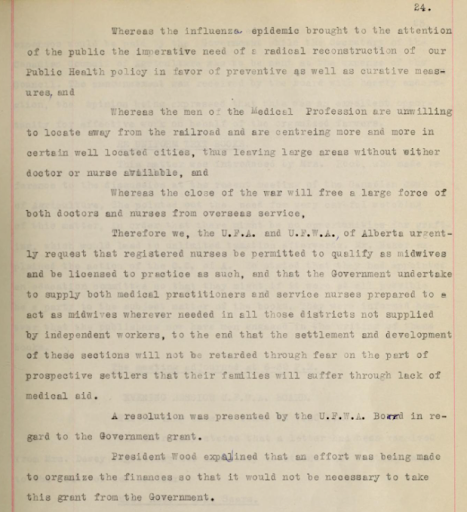

In 1924, Irene Parlby and Provincial Health Minister, George Hoadley, called attention to the fact that Alberta also had the highest postoperative death rate in the country. The inaccessibility of healthcare was urgent and could no longer be ignored. One of the main issues that the UFWA identified was the lack of incentives for doctors to migrate away from urban centers. In a December 1918 meeting with the president of the Alberta Medical Association, Mrs. Parlby sympathized with the country practitioners, acknowledging their strenuous lives, but was firm that there needed to be some form of resolution. One solution was that registered nurses be given license to attend maternity cases in districts where it was not possible to procure a doctor. Despite a dismissal from the Medical Association’s president, the UFA and UFWA formed a joint resolution to urgently request that registered nurses be permitted to qualify as midwives and be licensed to practice as such. Though, this was only one of the many goals the UFWA had for social welfare in the province.

(UF 2014.0010.01. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/theufwa2116ufoa/page/n49/mode/2up.)

Recognizing the challenges that travel posed to most rural families, the UFWA began lobbying the Department of Public Health to provide medical inspection equipment in every school. They also requested that all nurses be given training in children’s examinations. Consolidating school and physician checkups in this manner helped to ensure Alberta’s children were not only receiving treatment and immunizations, but they were also educated on how to prevent and avoid illness. UFWA members understood that ‘health’ extended beyond medicine and physician care, and that preventative measures and other systems of support were imperative to an individual’s wellbeing. One such example is that of Mr. Pete Van Maarion from Cavendish, Alberta who, after being denied aid from the Red Cross, was assisted by the UFWA Local. Unable to work while attempting to care for his frail wife, newborn, and young children, the farmer had no way to support his family. By providing them with this community assistance, the UFWA helped ensure the young family’s welfare. Furthermore, through this case UFWA board members realized the poor state of communication between the Provincial Government and the Red Cross. It also demonstrated the failure of provincial officials, tasked with investigating the conditions of rural citizens requesting help, to submit thorough reports and get these individuals assistance. Mrs. Field, the UFWAs Convener of Health, then brought these concerns up with the Deputy Minister of Health, Dr. Laidlaw, to ensure Albertans had better access to support.

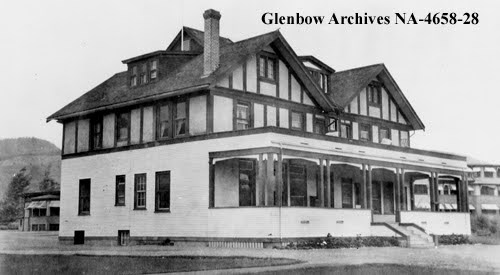

However, not every attempt was met with complete success, and compromise was sometimes necessary. As soldiers posted overseas in the First World War returned home, the number of tuberculosis cases gradually began creeping up and Alberta was hit particularly hard. Recognizing that the disease disproportionately affected those of lower income and spurred by a request from the Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis, in January of 1920 the UFWA drafted a resolution and began lobbying for civilians and returning soldiers to be given free treatment at the newly built government sanitorium in Bowness (pictured below). Eventually it was decided that municipalities would be responsible for the balance of the cost after government subsidies, which in 1929 was equal to about half the $2.93 per diem cost. While not ideal, it was still something. Incidents like this would have further motivated the UFWA’s impetus for state funded medicine to ensure the Province would provide treatment for its most vulnerable. Though, prior to this, a solution was still required for the nearly 60% of Albertans living outside of urban centers with little-to-no access to healthcare.

“Administration building, Sanatorium, Keith, Alberta.”, [ca. 1920], (CU1126785) by Unknown. Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Having lobbied persistently for the implementation of traveling clinics and dentists, the UFWA’s resolutions were finally met with success in 1924, as the Department of Health set up a handful of experimental rural clinics. Repeating these clinics in 1925 and 1926, by 1927 requests for their services were so numerous that the Department had to devise a more thorough plan of action to carry on the work. UFWA Locals alongside school administration typically took on the role of organizing the visits in their districts. The clinics provided rural towns access not only to physical examination, but to dental treatments and even surgery. From 1924 to 1929, the Traveling Clinic held 184 clinics, inspected 24,000 children, and performed 4,520 operations, among other things.

One of the potentially surprising causes that the UFWA backed was to amend the criminal code so as to legalize contraceptives, allowing women control over their reproductive rights. In the early 1920s they began lobbying for the creation of family planning clinics and for, “the speedy removal of all barriers due to legal restriction, traditions, prejudice, or ignorance which now prevents parents from access to such scientific knowledge on this subject as is possessed by the medical profession.” Recognizing that the medical obfuscation which had historically shrouded women’s health and reproduction resulted in a much higher risk to both mother and child, the UFWA wanted both education and support for their communities. The movement was slow to gain momentum, but by 1940 many Canadian physicians joined in and began staffing such clinics.

(Top) Jean Field, UFWAs Convener of Health and second Vice-President, and John MacEachern, Ph.D (Bottom) Dr. George Mason and Dr. Edgerton Pope

Information retrieved from Robert Lampard’s Alberta’s Medical History: “Young and Lusty, and Full of Life”

Photo retrieved from https://www.wikiwand.com/en/John_M._MacEachran

However, as with many facets of history, not all of the UFWA’s motivations align with modern views on equality and respect. While providing women with birth control and education about their bodies, as well as health checkups for school children, was both progressive and beneficial for the majority of Albertans, it was unfortunately rooted in a heavily problematic movement. The Social Hygiene movement gained momentum in the beginning of the twentieth century as fears in Canada, the United States, and Britain mounted around the supposed degeneration of the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ race – a socially constructed category for white, protestant, English speaking people. Ensuring the health of these individuals was paramount in order to maintain white dominion. Family planning clinics helped in spreading disdain and fear against venereal disease and those infected with them, and inspections on school children monitored them for traits which could be perceived as ‘defective’. Social Hygienists, like Nellie McClung, Emily Murphy, and Irene Parlby, among others, adopted eugenic beliefs which associated things like venereal disease with certain hereditary traits, as opposed to bacteria, and linked their spread to deviant behaviour. One of the solutions proposed to curb the proliferation of these individuals deemed to be ‘undesirable’ was sexual sterilization. Under the Sexual Sterilization Act of 1928, those with intellectual disabilities, or those deemed to be mentally unfit, could be sterilized to prevent them from procreating. If you’d like to know more about eugenics in Canada and the Sterilization Act, which was not repealed until the 1970s, see here:

While it’s important to be held accountable for harmful actions, it’s also important to recognize that both rural and urban Albertans also benefited from many of the UFWA’s efforts. From the organization’s inception, State Medicine was one of the principal concerns to ensure that everyone, no matter their status or finances, could access medical treatment, hospitals, and physicians. In April of 1935, nearly two decades of work finally came to fruition, as the Minister of Health introduced the Alberta Health Insurance Act. This legislation helped in paving the way for the universal and public healthcare system implemented by the Canadian government, with the Medical Care Act in 1966, reaffirming the UFWA’s statement over 45 years earlier, that “it is the duty of every civilized people to care for their sick.”

Works Referenced and Further Reading:

Bow, M. R. “Public Health Services in Alberta.” Canadian Public Health Journal 21, no. 12 (1930): 590–600.

Ferguson, R. C., and R. G. Ferguson. “Activities in a Province-Wide Programme for the Control of Tuberculosis.” Canadian Public Health Journal 26, no. 3 (1935): 130–37.

Lampard, Robert. Alberta’s Medical History: “Young and Lusty, and Full of Life”. Red Deer, Alberta ; Robert Lampard M.D., 2008.

Liu, Kimberly E, and William A Fisher. “Canadian Physicians’ Role in Contraception from the 19th Century to Now.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 24, no. 3 (2002): 239–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)30224-9.

MacMurchy, Helen. “On Maternal Mortality in Canada.” Public Health Journal 16, no. 9 (1925): 410–16.

McGugan, A C. “The Alberta Health Insurance Act.” Canadian Public Health Journal 26 (1935): 372–76.

McKinlay, Clare Mary. The Honorable Irene Parlby. Edmonton, Alberta: The University of Alberta, 1953. Dissertation

https://archive.org/details/honorableirenepa00clar/page/n75/mode/2up.

McLaren, Angus. Our Own Master Race : Eugenics in Canada, 1885-1945. Toronto, Ontario ; University of Toronto Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442623316.

Riddell, Justice. “Canadian Social Hygiene Council: PRESIDENT’S ANNUAL ADDRESS.” Public Health Journal 17, no. 6 (1926): 277–84.

“U.F.W.A. Executive, Board and Convention Minutes 1915 – 1925.” Fonds 2, Series 1, File 16. In custody of the United Farmer’s Historical Society. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/theufwa2116ufoa/page/n49/mode/2up.

“U.F.W.A.Minutes 1926 – 1931.” Fonds 2, Series 1, File 17. In custody of the United Farmer’s Historical Society. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/theufwa2117ufoa.

Written by Zowie Jones, Mount Royal University practicum student