Prohibition may not be a topic of much concern for everyday Albertans, but we are coming up on the 100th anniversary of Prohibition ending in Alberta which has sparked interest here in the United Farmers Historical Society (UFHS) archives. While there are popular events within American Prohibition and infamous characters like Al Capone and the various rum runners that live on in history as some of the most violent and dangerous people of the 20th century, this notoriety is not as prevalent in Alberta’s Prohibition era. Despite this, there are ties with the Alberta government, today’s culture, and even the creation of the provincial police to Prohibition. That being said, one cannot go far into Alberta’s history without running into the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA), who had an integral role in the maintenance and popularization of the Prohibition movement, and ultimately Prohibition’s downfall.

First UFA Board of Directors, 1909 (UN 23-1)

As people began to settle Alberta in the late 18th century, families quickly discovered how difficult rural life was in this climate. Many felt the need to let loose and socialize, and the saloon became the perfect place to do so.1 However, saloons began to develop a reputation as being dangerous, not only for the men who participated in drinking culture, but for their families as well. The threat of instability that alcoholism created, impacted the families who depended on working men, and as there were few options for help with alcoholism at the time, the desire for change and control took over.2

The concept of ‘going dry’ began to spread throughout North America at the beginning of the First World War in 1914 (however, attempts to control alcohol were happening even before this). This was because the need for food trumped the want of alcohol. Food supplies that were needed even more in a time of war were also being used to make alcohol (such as grain and barley) and the troops needed food if they were to keep fighting. In response to this, the British implemented a Liquor Law, and as a Commonwealth country, Canada soon followed suit.

“Hillhurst Presbyterian Sunday school group promoting prohibition/temperance, Calgary, Alberta.”, [ca. 1912-1916], (CU184045) by Unknown. Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

“[Prohibition] peaked after 1900 amid rising concerns about public health, family problems, and the power of producers to entice overuse.”3 Along with these concerns, Christian religious groups were also rallying for the control of alcohol, with the popularization of the temperance movement. There are ties between Christian morality and the desire to maintain an upstanding character in Western society. This relationship was seen as imperative to a successful country where the ‘right’ type of people would want to come and settle. Specifically, “Alberta was eager to outgrow its Wild West image and promote the Prairies as a land of industry, safety and orderly society – a place to raise a family and a farm in sobriety.”4

On July 21st, 1915, a referendum was called due to a petition that received nearly 24,000 signatures to enact a Prohibitory Liquor Act .5 The referendum ultimately found that “The Dry vote won […] with 58,000 votes, while the Wets drowned their sorrows with 38,000.”6 On June 1st 1916, Prohibition was enacted in Alberta. The government at the time was led by Premier Arthur Sifton who was in office from 1910 to 1917. Within this time, the UFA were becoming more involved in politics, lobbying and campaigning government to take farmer’s concerns seriously. Also in 1915, the United Farm Women of Alberta formed and voiced their concerns including advocating for rural healthcare and of course, Prohibition.

United Farm Women of Alberta Board, 1921 (UF 2004.0037.48)

The referendum showed that excessive drinking was a concern for the people of Alberta. Woman-run organizations like the United Farm Women of Alberta (UFWA) and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) were imperative to the promotion and popularization of the Prohibition movement. However, challenges arose once the Liquor Act had been finalized and Prohibition began. The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) were tasked with maintaining Canadian law in the scattered settlements of Western Canada. But when it came to enforcing Prohibition, the Mounties were “…notoriously lax”. A. Bowen Perry, the Commissioner of the NWMP at the time, felt that enforcing Prohibition was a losing battle.7 Perry was disgruntled by the chaos and the non-uniformity that the Western provinces were going through, as they all had different plans for Prohibition, and people had varying ideas of how they wanted their province policed and protected. Perry’s belief was that if the province wanted the job done, they could deal with it themselves!

“North-West Mounted Police officers at Regina, Saskatchewan.”, 1895, (CU184687) by Unknown. Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary. A. Bowen Perry is fourth from the left in the back row.

Tension between the NWMP and the Alberta government and populace grew, and the NWMP ultimately opted to focus on law and order in other parts of Western Canada. This led to the creation of the Alberta Provincial Police (APP) in 1917 and the officers who served were given quite a long list of duties including prosecutors, veterinary assistants, and even acting as the “town’s father confessor” when required.8 However, the biggest responsibility on the minds of the newly formed APP was enforcing Prohibition, a momentous challenge since alcohol had become so embedded into Western culture with saloons and the rural lifestyle.

When Premier Sifton left office, Charles Stewart became Alberta’s next Premier from 1917 to 1921 and Prohibition continued. However, in the election of 1921, Stewart was swept out of office in favour of UFA candidates that saw the UFA form a majority government. A historic win for farmers that had the UFA in office from 1921 to 1935. Early on in the UFA’s tenure, Prohibition became of interest to their government, and under UFA Premier Herbert Greenfield, Prohibition was increasingly tricky to navigate. As Gord Tolton writes in Deep Roots. Promising Future, “There was no way to keep a once legal substance out of the hands of those who wanted it.”9

Board of Directors, 1919. Back Row: H. Greenfield; H Higginbotham; Rice Sheppard. Front Row: Perren Baker; H. Wise Wood; Mrs. W. Parlby; W.D. Trego (UF 2004.0037.94)

Also in 1921 was a federal election and the UFA ran a slate of candidates. Potential candidate, Rice Sheppard was in favour of Prohibition and known for being active with the Temperance and Moral Reform League of Alberta. While running his candidacy for UFA, he became a vocal figure with a Prohibitionist’s political platform. One of his political pamphlets read, “…special features of [his] platform are as follows: … The Strict enforcement of Prohibition measures throughout the Dominion.”10 Sheppard was known for having quite the strong personality, and he was also one of the founding UFA board members in 1909. However, Sheppard was ultimately not chosen as the UFA candidate and correspondence records show that he even was requested to be removed from the organization after a political controversy arose.

Read more about UFA in politics here

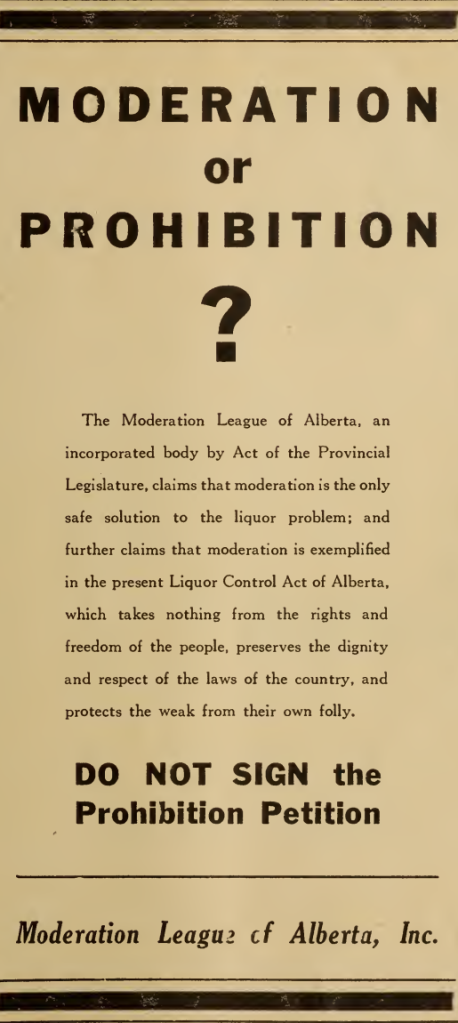

In Alberta, Premier Greenfield saw first hand the complications with the APP enforcing Prohibition, including the dangers of rum-running (see the story of Emilio Picariello). In addition, ‘prescriptions’ for alcohol were increasing with society’s desire for booze and there seemed to be no end to the issues that Prohibition had created. Perspectives on alcohol and Prohibition were beginning to change, and so too did people’s attitudes, including that of UFA MLAs and members. This is not to say that everyone abandoned their fight for Prohibition, some merely transferred to moderation (as seen in the ad pictured below from The U.F.A. published in 1931, years after the Prohibition referendum was a topic of interest).

The U.F.A Newspaper Volume 10, Number 1, page 21. January 2nd 1931.

Under Greenfield, safety concerns arose from people who lived in remote areas, as the Alberta Provincial Police did not patrol too far beyond urban centres, leaving rural folk feeling vulnerable and UFA members reported these issues during their meetings.11 These concerns led to the creation of the Social Service League (known as the Temperance and Moral Reform League in early 1917). This League encouraged people to report ‘liquor crimes’ to the authorities to help alleviate the still new APP force’s workload, but citizens were still hesitant to trust the APP to get the job done since they struggled to carry out their various roles. With the economic uncertainty brought on by the Great Depression, it became harder for the UFA government to justify funding the APP and they were disbanded 1932 and replaced by the Mounties. This was done under UFA Premier John E. Brownlee who had heard years of complaints from rural folks on how the provincial police force struggled, further warranting a change of approach to protection and safety.

“Prohibition committee outside Legislature Building, Edmonton, Alberta.”, 1931, (CU162433) by McDermid Studio. Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Perspectives that formed in the early 1900s assumed that society would be negatively impacted without proper order and good morals. Alcohol was seen as a disruption to this, and the families of people affected by alcohol abuse were viewed as suffering, therefore something had to be done. The United Farm Women of Alberta (UFWA), were one of the biggest supporters of Prohibition, including UFWA and Famous Five members Louise McKinney and Irene Parlby. In October of 1923, a provincial plebiscite was called to determine if Alberta should continue Prohibition. In advance of this, Parlby stated in a speech to the women of Calgary “Women are going to vote for Prohibition because they know it is in the best interests of the people, physically, morally and economically; because they feel it is putting a higher standard on the laws of the country.”12

However, after eight years, on November 5th 1923, Prohibition was voted out of the Alberta Legislature, and by May 1924 it was repealed under the UFA government. Activists including Irene Parlby were unhappy with this ruling, but as power shifted with public concerns a new era of politics emerged. The UFA government saw other concerns rising and rural issues more pressing which made enforcing Prohibition seem less important.

This period in Alberta’s history is interesting and enlightening, and as the centennial of Prohibition being repealed approaches, we can look to the past to view the cultural change of how we view substance use and its impact on society. This can be argued for Canada and the USA, as the effort to control a substance that was used for a wide variety of reasons, seemed near impossible (and was proved as such). This part of Alberta’s history is an example of how integral and intertwined the United Farmers of Alberta is to early government, and political and social activism, that has shaped our modern society.

“Lady showing liquor flask in garter.”, [ca. early 1920s], (CU189985) by Unknown. Courtesy of Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Written by Autumn Waddington, Archives Assistant

Footnotes

- Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, “‘John Barleycorn Must Die’: An Introduction to the Social History of Alcohol,” in Drink in Canada: Historical Essays, ed. Cheryl Krasnick Warsh (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), 6. ↩︎

- Red Deer Express Opinion Authors, “The History of Prohibition Across Central Alberta,” Red Deer Express, Black Press Media, April 1st 2015, https://www.reddeerexpress.com/opinion/the-history-of-prohibition-across-central-alberta/. ↩︎

- W.J. Rorabaugh, Prohibition: A Concise History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 1. ↩︎

- Gord Tolton, Deep Roots. Promising Future (Calgary: UFA, 2009), 34. ↩︎

- Gord Tolton, Deep Roots. Promising Future (Calgary: UFA, 2009), 34-35. ↩︎

- Gord Tolton, Deep Roots. Promising Future (Calgary: UFA, 2009), 35. ↩︎

- Mary Frances Doucedame, “The Stormy, liquor-plagued birth of the Alberta Provincial Police,” in Alberta in the 20th Century: The Great War and Its Consequences 1914 – 1920, ed. Ted Byfield (Edmonton: United Western Communications Ltd., 1995), 265. ↩︎

- Mary Frances Doucedame, “The Stormy, liquor-plagued birth of the Alberta Provincial Police,” in Alberta in the 20th Century: The Great War and Its Consequences 1914 – 1920, ed. Ted Byfield (Edmonton: United Western Communications Ltd., 1995), 268. ↩︎

- Gord Tolton, Deep Roots. Promising Future (Calgary: UFA, 2009), 23. ↩︎

- The Progressive Policy of the Labor-Farmer Candidate, Rice Sheppard, 1921, UF 2002.0049.24, Fonds 1, Series 4, File 10, Political Correspondence and News Clippings, United Farmers Historical Society Archives, Calgary Alberta: Page 1. https://archives.ufa.com/permalink/descriptions1598. ↩︎

- Mary Frances Doucedame, “The Stormy, liquor-plagued birth of the Alberta Provincial Police,” in Alberta in the 20th Century: The Great War and Its Consequences 1914 – 1920, ed. Ted Byfield (Edmonton: United Western Communications Ltd., 1995), 265 Note 3. ↩︎

- J.B.K., “Hon. Irene Parlby on Forthcoming Plebiscite: In Able Address Presents the Case for ‘Clause A’–Declares Public ‘Mesmerized by Phrases,’” (Calgary: United Farmers of Alberta, October 15th 1923) United Farmers Historical Society Archives. The U.F.A. Newspaper Vol.2 No. 19, 14. https://archives.ufa.com/permalink/theufav2n19ufoa-14. ↩︎

Formal Bibliography

Doucedame, Mary Frances. “The Stormy, liquor-plagued birth of the Alberta Provincial Police.” In Alberta in the 20th Century: The Great War and Its Consequences 1914 – 1920, edited by Ted Byfield, 264-279. Edmonton: United Western Communications Limited, 1995.

J.B.K. “Hon. Irene Parlby on Forthcoming Plebiscite: In Able Address Presents the Case for ‘Clause A’–Declares Public ‘Mesmerized by Phrases.’” Calgary: United Farmers of Alberta, October 15th 1923. United Farmers Historical Society Archives, The U.F.A. Newspaper Vol.2 No.19. https://archives.ufa.com/permalink/theufav2n19ufoa-14.

Political Correspondence and News Clippings. United Farmers of Alberta Fonds (1909-1948). United Farmers Historical Society Archives, Calgary Alberta.

Red Deer Express Opinion Authors. “The History of Prohibition Across Central Alberta.” Red Deer Express. Black Press Media, April 1st 2015. https://www.reddeerexpress.com/opinion/the-history-of-prohibition-across-central-alberta/.

Rorabaugh, W.J. Prohibition: A Concise History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Tolton, Gord. Deep Roots. Promising Future. Calgary: United Farmers of Alberta, 2009. https://archives.ufa.com/viewer/deep-roots-promising-future?p=12&type=static.

Warsh, Cheryl Krasnick. “‘John Barleycorn Must Die’: An Introduction to the Social History of Alcohol.” In Drink in Canada: Historical Essays, edited by Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, 3-26. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993.

Very interesting read especially the challenges of the provincial police service and vulnerabilities of rural communities. Certainly some learnings from the past for today.

LikeLike